Other pages, in T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order:

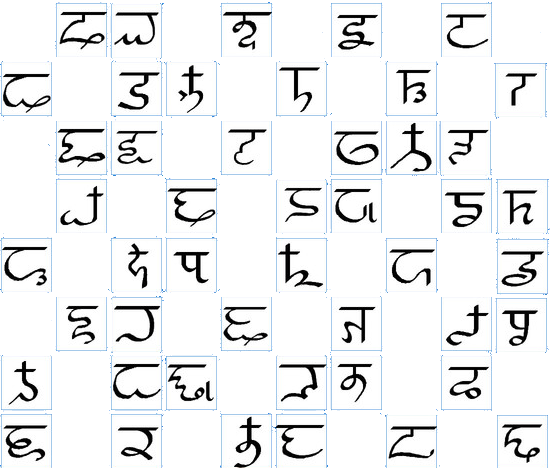

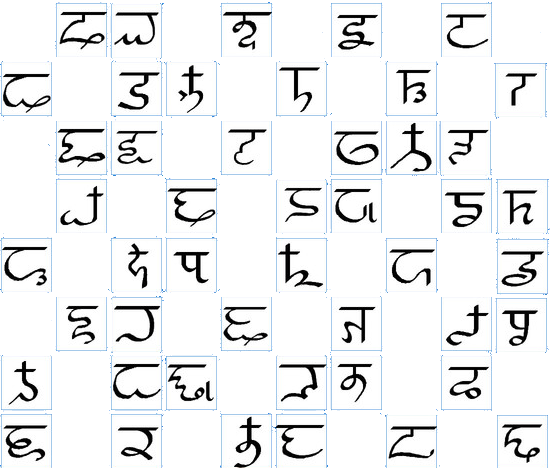

B P D́ T́ D T G K Q Ĵ C V́ F́ V F Ď Ť Z S Ž Š Ĝ X H M *M Ń *Ń N *N Ǹ *Ǹ L *L R *R Ĺ *Ĺ Ř *Ř W *W J *J A Â E Ê I Î O Ô U Û Y Ŷ AI AO IU OI ÂI EI Ē Ø

The entries in most dictionaries are words. In a dictionary of American English, one might find the word "fedora", followed by a definition of what a fedora is, perhaps with a picture of that kind of hat. Since English is rarely pronounced as it's spelled, English dictionaries usually include a guide to how the word is pronounced. Synonyms may be listed, as "hat", "chapeau", or even "sombrero". There may be etymological information about the origins of the word, and when it was first used in English. While the compiler of the dictionary may include whatever information desired, the core of a regular dictionary is a listing of words in that language's alphabetical order, and for each word, a definition of the word. The greatest dictionary of the English language is the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) published over the years by the Oxford University Press. It's no longer published on paper, but is available to subscribers online.

A bilingual dictionary, such as the Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD), correlates words of related meaning across two languages. The Pocket Oxford Latin Dictionary, for instance, has a Latin-English section, and an English-Latin section. One of the words in the first section is lyra, ae f lyre; lyric poetry; Lyre (constellation). This tells the consultor of the dictionary that the Latin word lyra is a feminine word of the first declension, and means a lyre or lyric poetry; and that it's a constellation as well. For a compact, inexpensive dictionary of Latin, that's more than enough. In the English-Latin section, under "lyre" we fomd cithara and lyra.

While many languages have writing systems based on Latin letters, such as English does, other languages have their own, independent letters, such as Greek; and the Slavic languages, especially have their own alphabets based on Greek latters. These languages have their own alphabetical orders, and a Greek dictionary, or a Greek-English dictionary, will list its words in that order.

The T́uliǹgrai Etymological Dictionary, or T́ED, is an etymological dictionary of the T́uliǹgrai language. It has an online page for each letter of the language, and on each page, lists the roots of the language. Under each root appears a selection of stems, and for each stem, the word that corresponds to it. Thus the basic entry is a root, not a word; and, of course, pages and entries are in T́uliǹgrai alphabetic order. The T́ED is one of a pair of works. The other part is "T́uliǹgrai Described", which details the alphabet, grammar, syntax, and other particulars of the language.

T́uliǹgrai is an artificial language. Though derived mostly from an earlier natural language called Eretiǹgrai, it was consciously designed according to a number of principles, rigorously applied. Chief among these is the framework of roots, stems, and words.

A root is a core of meaning. While a T́uliǹgrai root was chosen from a number of Eretiǹgrai words with related meanings, it's not a word itself. For example, the Eretiǹgrai noun ehod means "a stone, a rock"; the transitive verb hod means "to kill someone by throwing stones at him or her". The adjective hoda means "stony, stonelike", and the adverb hode means "stonily, in a stony manner".

Thus a natural language like Eretiǹgrai can have a root like -hod-, inferred historically by the existence of words such as ehod and hoda, and by identical or similar words in Hekai, Gêθai, and other languages descended from Mižinai. But the root itself isn't expressed in the language, though an actual word may have the same form as the root; the hypothetical root -hod- isn't the same as the actual verb hod. The verb hod is inflected for tense, voice, and mood; the root -hod- is not.

Furthermore, in a natural language, the expression of a root may be inconsistent and unpredictable. Eretiǹgrai adjectives may end in -a, -ai, or -annai, and Eretiǹgrai nouns may begin with any vowel, or even none.

A stem is the root plus the determining affix that transforms it into a word. For instance, HOD- plus E gives HODE, the stem of the count noun ehodai, a stone; HOD- plus O gives HODO, the stem for the adjective hodol, stony or rocky.

Like roots, stems play no part in speech or writing. However, they're useful in the design of the language, and if you list meanings by stems, they'll be grouped together. If you list them by words, they'll be scattered throughout the dictionary: all the count nouns under E, all the mass nouns under Ê, the animate nouns under Ē, and so forth.

Outside of the narrow field of the design and construction of the language, where roots and stems play a part, actual speech and writing is expressed through words. Most words are two or more syllables long, and consist of an atom of meaning (root) transformed in a regular fashion by the addition of affixes (prefixes and suffixes).

T́uliǹgrai is an inflected language; most words are inflected (changed) to show how they're used in the sentence in which they occur. Count nouns are prefixed to show gender, and suffixed to show noun case and number. Verbs show mood (indicative, interrogative, subjunctive, and more), tense, and other things. Adjectives and adverbs are prefixed with the particles DA, DE, DE, etc. to show comparison and intensity.

Some words, especially interjections, prepositions, and conjunctions, are particles. Particles may not be formed from roots or stems, may have no regular form, and may be any number of syllables, even one.

Phrases may be expressed as compound words, purely as a matter of style or usage. The phrase Eihôvai ēkišê, "the study of cats", means the same as the phrase eihôvai kišol, "cat study, feline study", or the compound word eikišahôvai, "catstudy, felinology". It's all a matter or style, or even whim.

The vowel at the end of the modifying stem, the "cat" part in the example above, is usually -A, by convention. In Eretiǹgrai, A(L)' was the mark of the genitive, partitive, and ablative noun case, which are three different noun cases in T́uliǹgrai, marked by A, AO, and Ê respectively. In the earlier language, al'akish could mean "of a cat", "belonging to a cat", "part of a cat", or "about a cat."

Different human languages have different vocabulary sizes, depending on many different factors. English has a huge vocabulary, due to the historical fact of absorbing huge amounts of Norman French and Latin into its basic Germanic inventory. It also coins new words readily, unlike Latin, which tends to assign a new meaning to an existing word. It also accepts words from other languages, such as coyote, chocolate from Nahuatl (by way of Spanish), pasha and fez from Turkish, abyss from Sumerian (by way of the Bible), and so forth/ Depending on what you count as a word, estimates of words in English range from 150,000 to 1,500,000, with 500,000 to 750,000 words being quite likely.

Wikipedia's estimate (guess?) puts Korean at 1,100,373 words; Japanese at 500,000; Italian at 260,000; English at 171,476; Russian at 150,000; Spanish at 93,000; and Chinese at 85,000 words. These numbers seem unrealistically low, but without knowing their sources, and what they "count" as a word, impossible to verify, for good or ill. As a general rule of thumb, perhaps it's not unreasonable to assert that a language spoken all over the world, by a large population of native speakers, probably has between 500,000 to 1,000,000 words, however we define a word.

It isn't my intention with the T́uliǹgrai Etymological Dictionary to list every single word in the language. For one thing, assuming there are 1000 roots in T́uliǹgrai, the number of two-roots would be one million words, all of them legitimate words in structure, however ridiculous they might be in meaning. Add the infix -ST-, which means "a group, bunch, set, or collection" to those million compound words, and now you have two million words, counting only compound words with only two roots compounded!

Instead, I've chosen a standard set of stems to list for each root, 16 in all. These don't list every possible word for a root, but a representative set. Look at any page in the Dictionary, and you will see, for each root, the following stems:

This is by no means all the words in the language, but it's a good start. By the time I reach 1000 roots, that would make 16,000 words in the Dictionary; 6000 roots, about 96,000 words. At a rate of one root added per day, that will take about 5500 days, or until sometime in 2034. Something to look forward to!

I discovered the writing of Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1962. Tarzan was a movie character to me, showing up on the TV regularly in reruns of old black-and-white movies, and occasionally in badly-drawn comics books. But, in an airport on the way to Guam, I picked up "Tarzan of the Apes", and you can only spend so many hours staring down at the clouds on a long, long trip across the Pacific on the propellor-driven aircraft. I read the first Tarzan book, and the first John Carter book, on that trip.

The most interesting thing about both Tarzan's Africa and John Carter's Mars was the languages ERB had invented. I'd never been taught any languages in school, so aside from English and Latin, these were the first languages I'd ever encountered. I made a list of mangani words like gomangani, bundolo, and kreegah. Heck, the name "Tarzan" itself means "White Skin"! I added words from Barsoom, and words from other science-fiction novels and stories, as I encountered them.

This process continued until I had too many words to remember in my head, especially after I dared to make up words and add them to the list, just as if I were a writer, myself! Adding new words, whether from a book or from my head, also required me to rewrite the whole list, to keep it in order. This was good for reviewing the list, but a big pain on the other end of my anatomy.

Catholic school circa 1964 introduced me to the Roman calendar by way of a priest's breviary, the one time he showed it to me, and I recall sitting in class and doodling letters to write my language in, plants and animals, and bits of history. By the time my family moved from Spokane to San Diego, I had lots and lots of disconnected bits and pieces, written and drawn on scraps of paper.

The word list, at least, got organized by copying the words onto 3x5 index cards, and keeping them in a metal, greyish-green metal card-file box. About a year later, there were too many cards for the box, and something more was needed. The San Diego Unified School System, excellent in most respects in those years, stopped teaching Latin. Among the stuff I acquired from the cheap bookstores that ran up and down Broadway in downtown San Diego was a lot of Latin textbooks, and other Latin instructional material. On of these was a set of "Latin Vocabulary Cards".

These cards were 3.5 inches wide by 1.5 inches tall each, with the Latin on one side, and the English on the other, for use as flash cards. I took them as a model for my own new dictionary. I made two boxes, each 8.75 inches long, 3.75inches wide, and two inches deep, and cut enough cards to fill the two of them, out of unlined 20# paper. These cards were the same dimentions as the Latin cards. Then I made a box big enough to hold those two boxe side by side, out of white cardboard with a hinged lid, and covered that box with gold-colored shelf paper. The left-hand box listed words of the T́uliǹgrai language. The cards were separated into T́uliǹgrai letters by tabs, and the aspects were separated by cardboard separators covered with gold shelf paper; so under "B", for instance, came words beginning with "B", then the separator, then words beginning with "P". Since the cards were hand-written, writing all the T́uliǹgrai words and letters, on both the T́uliǹgrai-English cards in the left-hand box, and the English-T́uliǹgrai cards in the right-hand box, presented no technical difficulties.

So my first dictionary was the metal card-file box, long since completely copied over into the custom-made box of my high-school years. Call that Stage 1 and Stage 2 of my T́uliǹgrai dictionary. When I put together my first web site, around 2002, it included an online dictionary and glossary. This included every term, personal name, place name, and word that appeared in any of my stories on that web site, in any language. All the entries were in English alphabetical order, and T́uliǹgrai words weren't in T́uliǹgrai letters, but in the same transcribed letters used in the stories. Still, it was a working reference to keep me consistent. Call that Stage 3.

When I started my second web site in 2017, I started a new Dictionary. This was was etymological; the entries weren't words, but roots, and for each root stems and words. I knew what I wanted it to look like, but didn't know how to make it work that way on a computer yet. Gradually, I've figured most of those things out, and have gone back through the Dictionary,retrofitting features. Generally, I've been adding a new root each day, and fixing one or two existing roots to match. Stage 4 was complete, some time in September 2019, when I'd marked every stem and word as such with HTML tags, so that I could run macros to count how many roots, stems, and words are in the Dictionary.

From September through November I ceased adding new words while I converted the Dictionary to be like the one from high school. All the root files have been renamed, so that the computer will sort them by T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order, and special characters like T́ are now included, in file names and text alike, not as HTML code that a browser will display as a special character, but as the actual special character itself. This makes the text and file names easier to read, and the root entries much shorter. The files aren't in folders of the English transcription, but in folders which correspond to the T́uliǹgrai letters themselves. Everything in the Dictionary is now in T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order, not in quasi-English alphabetical order.

At the time of this writing, then, we are in Stage 5 of the Dictionary: everything appears on pages, one for each T́uliǹgrai letter, everything's in T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order, and the navigation bars at the top and bottom of each page work. We will remain in Stage 5 while I go through the Dictionary, adding a new root each day and fixing the existing roots to use special characters instead of transcriptions for special characters, placing the stem entries in T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order, adjusting the spacing between root entries, adjusting where clicking on a link takes you, and some other things. At one root per day, that'll take about 500 days, or roughly 17 months.

While I'm working on that every day, I'll be converting the letters of the alphabet into they're a font, which don't need to be cut, pasted, and the spacing adjusted by hand in an image processor. Once that's done, Stage 6 will involve preceding the existing root, stem, and word transcriptions with the same in the actual T́uliǹgrai characters. There will also be voice recording of the root, stem, and word entries, so you can click on one and hear how it's pronounced. Inserting gloss tags will allow a regular T́uliǹgrai-English and English-T́uliǹgrai bilingual dictionary to be generated from the T́ED periodically. I should also be possible to generate an Eretiǹgrai-English and English-Eretǹgrai bilingual dictionary from all the Eretiǹgrai vocabulary in the T́ED!

I need to write and scan the letters of the Horiel, and make a chart of how they differed among the various languages of the Krahos. Presently the only Horiel letters I have in electronic form are the bits used in "A Meeting at Κtûn."

As I go through the Dictionary in Stage 5, I need to go through my old, golden Stage 2 dictionary, and sort through all the words in it. Every word in it which isn't already in the current Dictionary needs to be added to the new one. Then the old dictionary will finally be replaced!

Other pages, in T́uliǹgrai alphabetical order:

B P D́ T́ D T G K Q Ĵ C V́ F́ V F Ď Ť Z S Ž Š Ĝ X H M *M Ń *Ń N *N Ǹ *Ǹ L *L R *R Ĺ *Ĺ Ř *Ř W *W J *J A Â E Ê I Î O Ô U Û Y Ŷ AI AO IU OI ÂI EI Ē Ø