The T́uliǹgrai Alphabet

by Leo D. Orionis

1. History of the alphabet

Earlier alphabets

The human colonists from the First Universe, the Mižinē, spoke a language, Mižinai, ancestral to

T́uliǹgrai. To write this language they used a collection of scripts. Iriel was used for all

formal documents, official records, and important occasions. Iriel, however, was originally the alphabet of a

completely different, older, syllabic language, and required some additional signs to represent Mižinai. For

ordinary occasions, therefore, a second script was used, called Horiel. The alphabetic Horiel

is the grandmother of the T́uliǹgrai alphabet.

As part of the breakdown of civilization following the explosion of the star Herâk, the Mižinai language

degenerated quite rapidly. Atoms of meaning became words, with fixed forms and fixed meanings. On the continent of

Loraon there were three main dialects of the new language: Hekai, on the islands of the Central Sea; Gêθai,

spoken on the northern coast of the sea, and Eretai, also called Eretiǹgrai, used on the southern coast of the

Sea. Constant trade between the speakers of these dialects kept them from diverging into three mutually

unintelligible langages. Hekai and Eretai overlapped on the southern part of Heki; Hekai and Gêθai in

the north of Heki; all three dialects, and a fourth minor one, on the rocky western coast of the Sea; and Hekai,

Eretai, and another minor dialect, on the eastern mouth of the Sea, and the Sentinel Islands beyond.

The written language degenerated as well. Iriel was discarded, or forgotten, and the new dialects were written

entirely in a form of Horiel. The characters were largely the same, but not entirely; the combinations of characters

used to spell consonant combinations and diphthongs varied as well; and a new set of numerals came into use.

An artificial system of writing for an artificial language

The new race, the Verē, wanted a language of their own, written in an alphabet of their own. As their leaders

were Eretiǹgrē, they took the Eretiǹgrai language and the Eretiǹgrai alphabet as the foundation

of their own. The new language, T́uliǹgrai ("The High Speech"), was designed to be perfectly regular, not

only in its grammar and syntax, but in the rules for forming T́uliǹgrai roots from Eretiǹgrai words,

and the rules by which verbs, nouns, adjectives, etc. were formed from roots. (This will be described under

grammar and vocabulary; right now, we're just discussing the alphabet.)

The T́uliǹgrai alphabet was based on the Eretiǹgrai horiel, with added structural rules, additional

characters replacing the multi-letter writing of many consonants and diphthongs, and another, completely original set of

numerals.

The Eretiǹgrai alphabet had a one-to-one correspondence with the phonemes of its simple consonants, and with

its six basic vowels, but that was all that could be said for it.

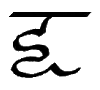

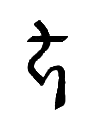

Characters did not indicate whether they were consonants, vowels, or numbers. T́uliǹgrai

consonants, it was decided, would face to the right; vowels would face left; and the new numerals would be distinguished

by each having a crossed ascender. (The numerals were adapted from Hekai numerals, different from those of the other

dialects.)

Lines of writing would run in a consistent direction. In Hekai and Eretiǹgrai, each bit of

text had to have a dot on the first line, marking the beginning of the line. If the dot was on the right, than the

first line was read from right to left, the next line from left to right, and this alternation would continue until the

end of the text, or until a new dot was encountered. Following Gêθai convention, every line of

T́uliǹgrai lettering would be read from left to right.

Similar sounds didn't have similar characters. Voiced/voiceless consonant pairs, such as V and F, D

and T, and Z and S, had entirely different letters that didn't reflect their relationship. Some consonants, which

hadn't been represented in Mižinai writing, were spelled as two or more letters, and not always the same letters

in different dialects. Voiceless nasals, voiceless liquids, and most diphthongs were spelled with sequences of more

than one letter; for instance, ē was spelled "aii".

The designers of the T́uliǹgrai alphabet took a ruthless axe to this thicket of thorny inconsistencies.

The sounds spelled with a single character in the Eretiǹgrai alphabet mostly were single sounds: B, P, G, K, L,

R, M, N, S, Z, etc. They designed letters for the voiced ones, sometimes rotating or flipping the original so that it

faced in the right direction. That gave them letters for B, D, G, V, Z, H, M, N, L, R, W, and J. Then they devised a

mark, based on the letter for H, that made a voiced letter a voiceless one, which gave them letters for P, T, K, F, S,

*M, *N, *L, *R, *W, and *J; the voiceless nasals, liquids, and semivowels had been written previously as HM, HN, HL,

HR, HW, and HJ. Thus they had letters for 23 consonants, using 12 letters and a marker for the voiceless ones.

Certain other consonant sounds which had been written with multiple letters had new letters created for them,

designed to resemble other consonants of a similar nature: D́, V́, Ď, Ĝ, Ń, Ǹ,

Ĺ, and Ř. Using these voiced letters with the voiceless marker gave them representations for T́,

F́, Ť, X, *Ń, *Ǹ, *Ĺ, and *Ř. An old form of A, suitably complex and facing the

right way, was adapted for Q, the glottal stop.

The remaining "consonants" were actually combinations of consonants, and should have been demoted to consonant

combinations, instead of letters of their own. But the alphabet designers bowed to tradition and adapted existing

letters for them, instead of introducing new combinations. This led to letters for Ĵ and Ž, and their

voiceless pair C and Š. All in all, that gave them 44 consonants, represented by 21 voiced signs, and 23

voiceless signs (the voiced ones plus the voiceless mark, plus H and Q which are always voiceless). Actual consonant

combinations still remained, such as STR, ZDR, SL, SR, SM, SN, etc., but the unnecessary and inconsistent combinations

of letters used to represent single consonants, such as DH, TH, NN, MH, HMH, HLL, etc, were eliminated.

Designing the vowels was much easier, not only because there were a lot fewer of them, but because the Loraonai

dialects already recognized the "broad" and "strait" vowel pairs, even though, like Mižinai, they didn't mark

them. For example, an A in a word might be an actual A sound, or an  sound, but the same letter was used for

both. The T́uliǹgrai designers adapted existing letters for the "broad" vowels A, E, I, O, U, and Y, and

adopted a mark (what we'd call a circumflex) to go above the same letters to mark the "strait" vowels Â, Ê,

Î, Ô, Û, and Ŷ. Thus 6 letters, with or without the circumflex, represented all 12 vowels.

The eight diphthongs weren't difficult to design. Some of the letters already existed, and only had to be turned

around, or changed slightly. The letter Ø was deliberately designed as a backwards R, the sound -ER being

regarded as a vocalic R, and spelled as an R without a preceding vowel in words like hnulr, "empty". What

was chosen as a diphthong and got its own letter, and what was left to be written as a pair of letters, was a

combination of tradition and vowel length. Vowels are short; vowels sequences are long, and diphthongs are in

between, except for Ē, which was a matter of tradition. To put it another way, if vowels were pronounced with

the length of a musical quarter-note, diphthongs were half again as long (dotted quarter note), and a pair of

vowels, like the interjections Ea! or Io!, were spoken over the length of a half note. (This will

come up under word stress, but that's a language topic, not an alphabetic one.) Anyway, if it was short, or

halfway between short or long, or Ē, it got its own letter.

Beginnings of syllables, and ends of closed syllables, weren't marked in any way whatsoever. The

only things dividing one word from another was a blank space between them, or in older writing, a dot in the middle of

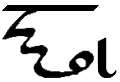

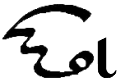

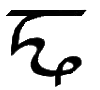

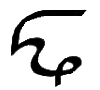

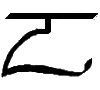

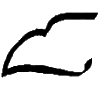

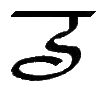

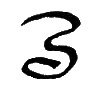

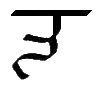

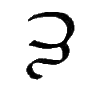

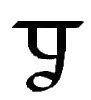

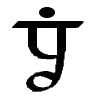

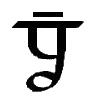

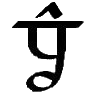

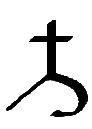

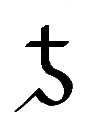

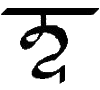

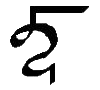

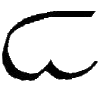

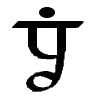

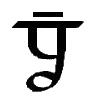

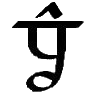

the line height. T́uliǹgrai letters have two forms. The first, marked with a

straight bar over the letter, is used when the letter occurs at the beginning of a word, or when the letter stands

alone, as in art. The second form, with a flag to the right for a consonant or to the left for a vowel or diphthong, is

used for everything else. The beginning of a syllable also marks the end of the previous syllable in most cases, since

most syllables are open. When a syllable is closed (ends with a consonant), the consonant is followed by a vertical

bar indicating no vowel after it. I mark this with a dash—when I remember to do so.

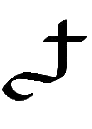

In the original design of the T́uliǹgrai alphabet, each consonant had four forms. The

first form was used when the consonant began the word, the second when the consonant began a syllable but not the

word. A third form was used for the second through nth consonants of a cluster, e.g., the D and R of the cluster

ZDR. A fourth form, resembling the second form flipped to face left, was used when a consonant closed a

syllable.

This was felt to be too much of a good thing, or maybe just too much, period. The third form was dropped and

consonant clusters are now shown as strings of the second form. The only remaining vestige of this scheme is the

voiceless sign, which was originally the third form of the consonant H. The fourth form was

dropped in favor of the second form followed by a vertical bar, one of the ways closed syllables were indicated in

Horiel, on the rare occasions they were shown at all (mostly in dictionaries).

Beginnings and ends of clauses and sentences weren't marked; there were no punctuation characters.

This is because Horiel wasn't meant to be a stand-alone script, but phonetic transcription for the words in Iriel,

which did have punctuation. Different punctuation marks were made up in different Loraonai countries; they weren't

at all consistent, and also changed over time.

T́uliǹgrai has two punctuation marks, which are full members of the alphabet. One of these faces to the

right and comes before an utterance (phrase, clause, or sentence), the other one comes after an utterance and faces

left. The first indicates that the following utterance is indicative, interrogative, exclamatory, or incredulous

(according to the markings above it), and might be considered the equivant of a period, question mark, exclamation

point, or interrobang. The second punctuation mark indicates a pause like a comma, semi-colon, colon, or period

(depending, again, on the markings above it).

Alphabetical order was completely arbitrary. The "alphabetical order" of the letters in

Mižinai, and its descendant languages, had nothing to do with what kind of sounds they represented (e.g.,

consonants, vowels, or diphthongs), how the sounds were produced in the mouth and throat, or where they were

produced.

The alphabetical order of T́uliǹgrai is the order in which the characters occur in the chart below:

the consonants, the vowels, the diphthongs, then the non-sound letters of the punctuation marks and the numerals.

Within the consonants, the letters are in order by what kind of sounds they are (stops, fricatives, nasals, etc.), and

within each of those, by where the sound is produced, from bilabial back to velar and glottal. Within each letter, the

voiced form comes first, and the voiceless form second.

The true vowels are in order from the center of the mouth (A), farther forward and up (E), up to the top front (I),

back along the top (O), and ending at the back of the mouth (U). Y, being both front like I but rounded like U, should

probably come between I and O; but entered the Mižinai language after its native five vowels, borrowed from the

same First Universe language as the Iriel syllabary. Thus it's traditionally (there's that word again) tacked on

after the others.

The vowel combinations come after the vowels, very roughly in the same order as their component vowel sounds. An

assortment of vowel-like leftovers follow, such as EI, which is not a true diphthong, but a letter for E followed by

I; Ē, the only long vowel in T́uliǹgrai; or Ø, which was represented in Iriel in

many different ways (ER, IR, UR, YR, and R). When the backwards-facing consonant forms were dropped (see above),

the backwards R was seized as the letter for Ø, removing the last irregularity from the letter shapes of

the written language.

2. Character chart

Consonants

Characters 1-23 of the T́uliǹgrai alphabet represent consonant sounds, some of which will be

familiar to English speakers. These 23 letters represent 44 different phonemes of the spoken language,

because 21 of them can be either voiced or voiceless; Q and

H are voiceless only.

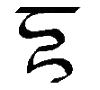

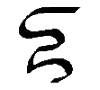

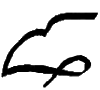

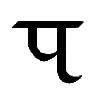

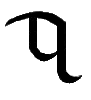

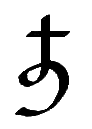

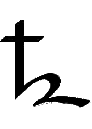

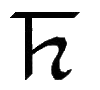

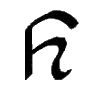

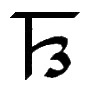

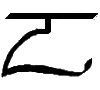

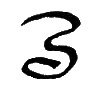

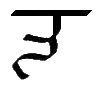

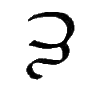

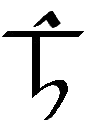

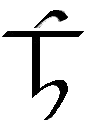

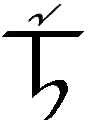

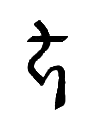

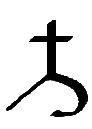

Each consonant character has two forms, as discussed above. These forms are shown in the second and third column of

the table below.

The Gloss column shows the symbols chosen to transliterate the consonants in English writing (such as this

web site). More on that after this chart. The voiced aspect is shown first (for example, "B"),

the voiceless aspect second ("P"). Voiceless aspects of

letters that are never voiceless in modern English are indicated by preceding them with

an asterisk, such as *N for a voiceless N. For consistency, and because many English speakers pronounce voiced and voiceless W the same, voiceless W in

T́uliǹgrai is rendered as *W instead of WH.

The last column of the table describes approximately how the consonants are pronounced, by reference to sounds in

English and other languages. When special coding is needed for the transcription, it's shown in brackets in

this column.

| |

Form 1 |

Form 2 |

Gloss |

Pronunciation and usage [HTML/Unicode]

(Click on unfamiliar terms for glossary) |

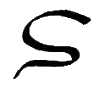

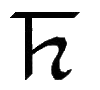

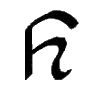

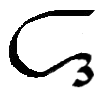

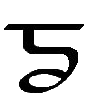

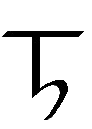

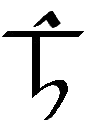

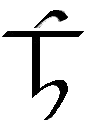

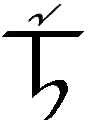

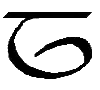

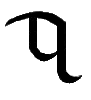

| 1 |

|

|

B, b

P, p |

Like English or Latin B. Letter name: Bo.

Like English P, except it can be aspirated

or not aspirated. Letter name: Pa. |

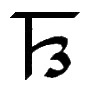

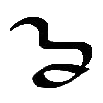

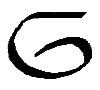

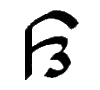

| 2 |

|

|

D́, d́

T́, t́ |

Dental D. [D́ = D́ d́ = d́] Name

= D́e.

Dental T; T́ can be aspirated or not

aspirated. [T́ = T́ t́ = t́]

Letter name: T́i. |

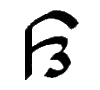

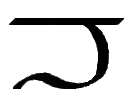

| 3 |

|

|

D, d

T, t |

Like English D. Letter name: Do.

Like English T, except T can be aspirated

or not

aspirated. Letter name: Ta. |

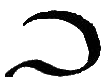

| 4 |

|

|

G, g

K, k |

Like English G as in "golf", never G as in "gentry". Letter name: Go.

Like English K, except K can be aspirated or not

aspirated. Letter name: Ka. |

| 5 |

|

|

Q, q |

Glottal stop; no voiced

form. Does not combine (no glottalized consonants). Letter name:

Qi. |

| 6 |

|

|

Ĵ, ĵ

C, c |

Ĵ = English J as in "Juliet". [Ĵ = Ĵ ĵ = ĵ]

Letter name: Ĵe.

C = English Ch as in "church". Letter name: Ci. |

| 7 |

|

|

V́, v́

F́, f́ |

V́ = Bilabial V, like B between vowels in Spanish, e.g., Caballo.

[V́ = V́ v́ = v́] Letter name: V́e.

F́ = Bilabial F, the voiceless form of V́.

[F́ = F́ f́ = f́] Letter name: F́i. |

| 8 |

|

|

V, v

F, f |

Like English V. Letter name: Vo.

Like English F. Letter name: Fa. |

| 9 |

|

|

Ď, δ

Ť, θ |

Ď = English Th as in "that". [Ď = Ď δ = δ],

Letter name: Ďe.

Ť = English Th as in "think". [Ť = Ť θ = θ]

Letter name: Ťi. |

| 10 |

|

|

Z, z

S, s |

Like English Z. Letter name: Zo.

Like English S, but doesn't turn into a Z at the end of a syllable.

Letter name: Sa. |

| 11 |

|

|

Ž, ž

Š, š |

Ž = Like English Z as in "azure".

[Ž = Ž ž = ž]

Letter name: Že.

Š = Like English Sh as in "shout". [Š š]

Letter name: Ši. |

| 12 |

|

|

Ĝ, ĝ

X, x |

Ĝ is a voiced velar fricative, a

sound not found in English. [Ĝ = Ĝ ĝ = ĝ]

Letter name: Ĝe.

X = Ch in Scottish Loch or German Ach, or Х in Russian

Хорошо. Not the same as English X, which represents KS.

Letter name: Xi. |

| 13 |

|

|

H |

Like English H. No voiced form. Does not combine with other

consonants, except that aspirated P, T, and K are written as P+H, T+H, and K+H, respectively. Never omitted

or "silent". Never occurs at the end of a syllable. Letter name: Ha. |

| 14 |

|

|

M, m

*M, *m |

M = English M. Letter name: Mo.

*M = Voiceless M. Letter name:

*Mi. |

| 15 |

|

|

Ń, ń

*Ń, *ń |

Ń = Dental N.

[Ń = Ń ń = ń]

Letter name: Ńe.

*Ń = Voiceless dental N.

[*Ń = *Ń *ń = *ń]

Letter name: *Ńi. |

| 16 |

|

|

N, n

*N, *n |

N = English N. Letter name: No.

*N = Voiceless N. Letter name:

*Ni. |

| 17 |

|

|

Ǹ, ǹ

*Ǹ, *ǹ |

Ǹ = Gn as in "gnaw", N as in "sing".

[Ǹ = Ǹ ǹ = ǹ] Letter name: Ǹe.

*Ǹ = Voiceless Ǹ, e.g., Kn as in "know", N as in "sink".

[*Ǹ = *Ǹ *ǹ = *ǹ] Letter name: *Ǹi.

|

| 18 |

|

|

L, l

*L, *l |

L = English L. Letter name: Lo.

*L = Voiceless L. Letter name:

*Li. |

| 19 |

|

|

R, r

*R, *r |

R = English R. Letter name: Ro.

*R = Voiceless R. Letter name:

*Ri. |

| 20 |

|

|

Ĺ, ĺ

*Ĺ, *ĺ |

Ĺ = Forward flap L.

[Ĺ = Ĺ ĺ = ĺ]

Letter name: Ĺe.

*Ĺ = Voiceless forward flap L.

[*Ĺ = *Ĺ *ĺ = &ĺ]

Letter name: *Ĺi.

|

| 21 |

|

|

Ř, ř

*Ř, *ř |

Ř = Reverse flap R.

[Ř = Ř ř = ř]

Letter name: Ře.

*Ř = Voiceless reverse flap R.

[*Ř = *Ř *ř = *ř] Name =

*Ři.

|

| 22 |

|

|

W, w

*W, *w |

W = English W. Never ends a syllable. Letter name: Wo.

*W = Wh as in whether, when, etc. Never ends a syllable. Letter name: *Wi. |

| 23 |

|

|

J, j

*J, *j |

J = English Y as in "yellow". Never ends a syllable. Letter name: Jo.

*J = Voiceless J. Never ends a syllable. Letter name: *Ji. |

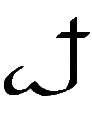

Vowels and diphthongs

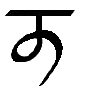

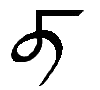

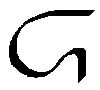

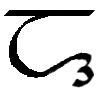

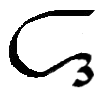

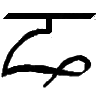

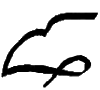

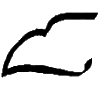

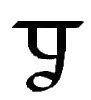

Characters 24-37 of the alphabet are vowels and vowel combinations.

Note that the consonant signs (above) all face to the right, while vowel

signs face to the left.

Each vowel has two forms. Form 1 is used when the vowel stands

alone, or when a vowel begins a word. Form 2 is used when a vowel

follows a consonant or string of consonants.

These 14 characters represent 20 sounds because the vowels each have

two aspects. The second one is distinguished by a circumflex (^)

above the vowel, both in the actual T́uliǹgrai and in the English

transcription of T́uliǹgrai.

Note that all vowels are short, in the Latin or Spanish sense of "short

vowel." They are "bitten off short" as in Spanish, not dragged out as in

English. The diphthongs (two pure vowel sounds combined) are

exactly twice as long as vowels, but still very short compared with their

nearest English equivalents.

There are no other vowel combinations in

T́uliǹgrai besides those shown! Interjections such as

Ea! and Io! are written with two vowels, and are two syllables

long, one syllable per vowel.

| |

Form 1 |

Form 2 |

Gloss |

Description of pronunciation [HTML/Unicode] |

| 24 |

|

|

A, a

Â, â |

A = Spanish A. Letter name: A or A levol (broad A).

= English A as in "hat". [ =  â = â]

Letter name: Â or A kapeol (narrow A). |

| 25 |

|

|

E, e

Ê, ê |

E = Spanish E. Letter name: E or E levol (broad E).

Ê = English E as in "pet". [Ê = Ê ê = ê]

Letter name: Ê or E kapeol (narrow E). |

| 26 |

|

|

I, i

Î, î |

I = Spanish I. Letter name: I or I levol (broad I).

Î = English I as in "bit". [Î = Î î = î]

Letter name: Î or I kapeol (narrow I). |

| 27 |

|

|

O, o

Ô, ô |

O = Spanish O. Letter name: O or O levol (broad O).

Ô = English U as in "put". OO as in "foot". [Ô = Ô ô = ô]

Letter name: Ô or O kapeol (narrow O). |

| 28 |

|

|

U, u

Û, û |

U = Spanish U. Letter name: U or U levol (broad U).

Û = English U as in "putt". [Û = Û û = û]

Letter name: Û or U kapeol (narrow U). |

| 29 |

|

|

Y, y

Ŷ, ŷ |

Y = Classical Greek or Latin Y. Letter name: Y or Y levol (broad Y).

Ŷ = German Ö. [Ŷ = Ŷ ŷ = ŷ]

Letter name: Ŷ or Y kapeol (narrow Y). |

| 30 |

|

|

Ai, ai |

English "long I" as in "kite", Latin AE, or Spanish AY, AI. Letter name: Ai. |

| 31 |

|

|

Ao, ao |

English OU as in "house", Latin or German AU. Letter name: Ao. |

| 32 |

|

|

Iu, iu |

English EW as in "pew", EU as in "feud". Letter name: Iu. |

| 33 |

|

|

Oi, oi |

English OY as in "boy", OI as in "noise". Letter name: Oi. |

| 34 |

|

|

Âi, âi |

English A as in "drag", "stag". [Âi = Âi âi = âi]

Letter name: Âi or Ai kapeol (narrow Ai). |

| 35 |

|

|

Ei, ei |

Spanish E followed by Spanish I; English AI as in "paid", AY as in "sprayed". Letter name: Ei. |

| 36 |

|

|

Ē, ē |

Double-length Spanish E, Latin long E.

[Ē = Ē ē = ē] Letter name: Ē or E

pitkol (long E). |

| 37 |

|

|

Ø, ø |

English EAR as in "early", ER as in "herd", IR as in "birth", OR as in "word", UR as in "fur".

[Ø = Ø ø = ø] Letter name: Ø. |

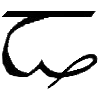

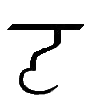

Punctuation

These next two characters punctuate the T́uliǹgrai

sentence. Instead of combining the type of expression (statement,

question, exclamation) and the length of the pause after each phrase or

sentence, T́uliǹgrai separates the two. Tone

(matter-of-factness, query, exclamation, or incredulity) is expressed at

the beginning by the first character, modified as shown. Juncture is

shown at the end of each phrase or sentence using the forms shown for the

other punctuation character.

| |

Form 1 |

Form 2 |

Form 3 |

Form 4 |

Gloss |

Description of usage

{Name of PNG file} |

| 38 |

|

|

|

|

"." "?" "!" "??!" |

Indicates mood of following phrase or sentence.

{38a, 38b, 38c, 38d} |

| 39 |

|

|

|

|

"," ";" ":" "." |

Indicates length of pause at end of the phrase or sentence

it follows. {39a, 39b, 39c, 39d} |

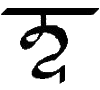

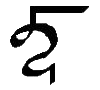

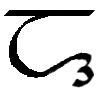

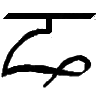

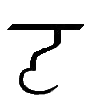

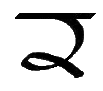

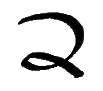

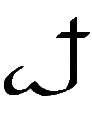

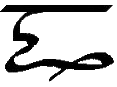

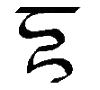

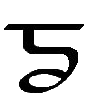

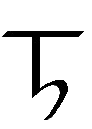

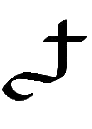

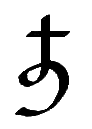

4. Numerals

The last eight characters of the alphabet represent the digits 1-7 and

0. Since T́uliǹgrai uses base-8 (octal) instead of

base-10 (decimal) arithmetic, there is no digit 8 or 9.

| |

Numeral |

Digit |

|

|

Numeral |

Digit |

| 40 |

|

1 |

|

44 |

|

5 |

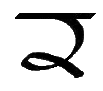

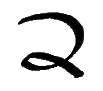

| 41 |

|

2 |

|

45 |

|

6 |

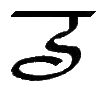

| 42 |

|

3 |

|

46 |

|

7 |

| 43 |

|

4 |

|

47 |

|

0 |

3. Transliteration

It was difficult, for a long time, to find a good transcription for T́uliǹgrai, because it has a lot more

sounds than most Terrestrial languages. I could have used a lot of combinations of letters to represent single

phonemes, as English does (CH, TH, GH, KH, HM, NN, RR, etc.), giving a completely false impression of what letters occur

in T́uliǹgrai, and how often they occur. Or I could have invented a lot of special letters, as Russian

did when it adopted the Cyrillic alphabet.

The latter would be the best solution, taking familiar letters and adding diacritical marks to them, so that each

sound is represented by a single character. Unfortunately, in publishing online, I was restricted to the

characters known to HTML, even more so then than now. Thus special characters such as N circumflex and T grave,

which I could use when publishing on paper, had to be replaced by strike-through characters and Greek letters like

Ξ and Θ. When I started the first version of this site, I struck the best balance I could.

Even so there were problems:

-

Identical forms:

Sometimes the "best" choice couldn't be used because the Greek and Latin alphabets have a common

ancestry. For instance, Rho would have been the (second-)best choice for a flap R, but a capital

Rho is identical in appearance to a capital P.

-

Wrong sound:

Sometimes a perfectly available letter would have been confusing because

I would have been using it for a sound unlike its original meaning. Using Pi for a flap R

could cause confusion because Pi is a P sound, not an R.

- Unfamiliar form:

Readers could also find completely unfamiliar letters difficult to read. Using Ξ for

the sound of J in Judge asked the reader to recognize Ξ and ξ before he could begin to remember

what they stood for.

- Word breaks:

A code like T́ (Ŧ) is treated by browsers as a letter like any other. Creating a letter

like T "by hand" with <s>T</s> is another matter. If it fell at the right margin, a browser

might choose to break it before or after either tag. Preventing this required lots and lots of

<nobr> and </nobr> tags. This was a lot of work and made it very hard to read the

actual text behind the web page. On top of that, <nobr> and </nobr> aren't allowed

under the strictest levels of HTML!

- Different Greek fonts:

Finally, not all Greek fonts look the same. The θ in Haθa might be larger than

the other characters in the word, smaller than the other characters, or boldly non-serif, depending on

the reader's browser and fonts.

Science (and Publishing) march on. Newer browsers implement newer versions of Unicode, giving me characters

I didn't have before. And since these are single characters from the same font as the regular letters, they

won't break strangely and they won't be different sizes or have different appearances.

In choosing Unicode letters for transcription, I made sure they'll appear without the reader or me needing to

select a special encoding or have a special font installed, whether in Konqueror, Firefox, Opera, or even Internet

Explorer. In the ideal transcription (still not quite possible, but almost!) I would've used an acute

accent (´) for sounds pronounced farther forward in the mouth, e.g., T́ for dental T,

in contrast to the alveolar T of ordinary English. Under the same principal of showing by

the diacritical mark how the sound differed from the familiar one, I would've preferred a grave accent (`) for sounds

farther back in the mouth, such as the velar N. Other differences are marked with a

circumflex (^), caron ( ̌ ), or tilde (~), in that order of preference, depending on what was

available.

With the discovery of combining marks, the ideal transcription is almost achieved. If you type a "regular" letter

followed by ̀, you get a grave accent over the first letter, such as Ǹ. This is pretty near ideal,

since the browsers don't break a line between the first letter and the combining mark; and the first letter reminds you

what kind of a letter it is (a nasal in this case) where an ordinary Unicode character like Ē gives you no

clue that it's an Ē. Other combining marks are ́ (combining acute accent), ̂ (combining

circumflex accent), ̌ (combining caron), ̄ (combining macron), and many more I felt no need to

use.

The only remaining glitch is that sometimes the combining diacritical mark hangs out too far to the left or right,

leading me to use a circumflex or caron instead; or the miniscule ("small letter") looks very different from the

majuscule with the same accent, which is why I'm using θ and δ for the lower-case forms of Ť and

Ď, respectively. Still, this is far and away the best transcription ever!

4. Glossary of linguistic terms

Alveolar

A sound made with the tongue at the back of the gum ridge (alveolus). In English, D/T and N are

alveolar. See also dental.

Aspiration

A voiceless stop (P, T, and K, for instance)

is aspirated if pronounced so forcefully that a distinct puff of air accompanies its utterance. Many

languages never aspirate their voiceless stops. On the other

hand, in Ancient Greek, unaspirated stops (represented by π, τ, and κ) were

separate phonemes from aspirated ones (φ, θ, and χ). Korean is the same, and also has

CH and aspirated CH phonemes (CH is phonetically T + SH). Modern English aspirates voiceless stops at the beginning of a syllable but leaves them unaspirated

elsewhere, as different forms of the same phonemes.

T́uliǹgrai distinguishes between aspirated and unaspirated P, T́, T, and K, but does not have

separate letters for the aspirated forms. Aspirated P, T́, T, and K are considered to be unaspirated

P, T́, T, or K followed by H, and that's how they're written. To avoid confusion with English combinations

spelled PH, TH, and KH, the aspirated stops are represented as in English with an apostrophe:

P', T́', T', and K'.

Bilabial

A sound made with the tongue between or just behind the lips (bi-labial, two lips). M and B are

bilabial.

Dental

A sound made with the tongue against the back of the teeth (dentalis, pertaining to the teeth).

Typically a language's D, T, and N will be either dental or alveolar, but

T́uliǹgrai has both sets.

Flap

A sound where the tip of the tongue flips forcefully once, rather than repeatedly (the latter is called

a trill). T́uliǹgrai has Ř, where the tongue flips from the front of the mouth to

the middle while making an R sound, and Ĺ, where an L sound is accompanied by the tongue flipping

forward from back to front.

Fricative

A consonant which doesn't stop the breath completely, but lets some of it slide on by; V, S, TH, and H are

some examples in English.

Glottal

A sound produced at or near the glottis, the little bulb that hangs down in the back of the mouth.

Found mostly in English in certain dialects; when John or Paul said he was a "Bea'l", the apostrophe

represents a glottal sound in Liverpool (Liverpudlian) English.

Glottalized

A consonant or vowel is said to be glottalized when said at the same time as a glottal stop. Found in

many African and American languages, but rare in Indo-European ones like English, French, Russian, or Greek.

Stop (Plosive)

A sound that brings the breath to a momentary full stop, hence the name. P, T, K, B, D, and G are all

stops used in English. Also called a plosive.

Velar

A sound produced with the back of the tongue against the soft palate (velum, which also means sail).

G and K are velar stops, and the GN in Gnarl and the N in missing is a velar nasal (unless you pronounce

them "narl" and "missin'").

Voiced

A sound made with the vocal cords vibrating. In English, all vowels are voiced, and many classes of

consonants come in both voiced and voiceless varieties. Old English had more voiceless consonants.

Voiceless (Unvoiced)

Voiceless is the opposite of voiced; the vocal cords are still, and there are usually some secondary

differences as well. When you keep the vocal cords still for an entire sentence, you whisper it.

Copyright © 1999-2018 by Green Sky Press. All rights reserved.